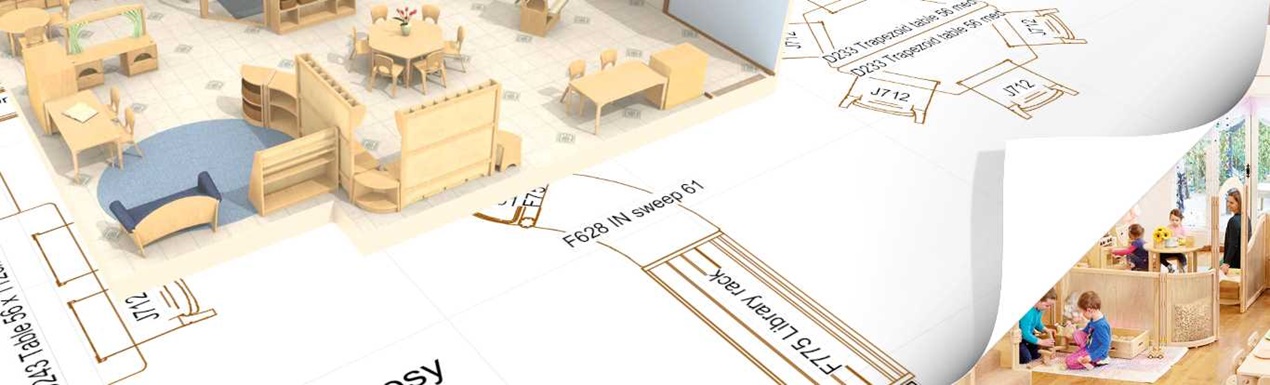

Creating indoor environments for young children

| June 2010An early childhood environment is many things. It's a safe place where children are protected from the elements and are easily supervised. And it's where the important activities of the day like playing, eating, sleeping, washing hands, and going to the bathroom take place. Beyond the basics, however, an environment for young children implements and supports a programme's philosophy and curriculum.

Philosophies like Montessori, for example, require well-designed classrooms with low shelves, four basic learning areas, and places for children to work and learn independently, and British infant/primary programmes have classrooms with a variety of rich learning centres, a cosy reading area with couch and carpet, and a lively science area that contains pets and plants. Conversely, an early childhood environment that lacks indoor gross motor play space and developmentally appropriate outdoor play equipment places a low priority on physical development in its curriculum (Wardle, 1989).

How does your environment support your philosophy and curriculum?

Since most early childhood philosophies stress the importance of play, hands-on-learning, and whole child development, a good early childhood environment supports these activities. Are there well-supplied dramatic play areas? Is there a large block area? What about sand and water activities, manipulatives, art areas, and reading corners? Is the space arranged in such a way that children can make noise while playing without disturbing children in other activities? Can children make a mess in the art area without destroying the books in the reading area?

Meeting children's needs

The young of every species have basic needs that must be met for them to develop and mature. Children are no exception. For children, these essential needs include warm, caring, and responsive adults; a sense of importance and significance; a way to relate to the world around them; opportunities to move and play; and people to help structure and support their learning. In the past, these needs were met at home and in the community, but now these needs are being met in our classrooms. According to Jim Greenman (1988), early childhood environments should be:

- Rich in experience. Children need to explore, experiment, and learn basic knowledge through direct experience. Indeed, childhood is a time when we learn firsthand about the physical world: the feel of water, the constant pull of gravity, the stink of rotten fruit, and the abrasive feel of concrete on a bare knee.

- Rich in play. Play provides a way for children to integrate all their new experiences into their rapidly developing minds, bodies, emotions, and social skills. Brain research supports this idea, stressing that children learn best through an integrated approach combining physical, emotional, cognitive, and social growth (Shore, 1997).

- Rich in teaching. The role of the teacher is critical in a child’s life. Children depend on teachers to be their confidant, colleague, model, instructor, and nurturer of educational experiences.

- Rich with people. Clearly children need lots of exposure to other people in their early childhood years. One of the greater weaknesses of Western society is that our children have less exposure to the diverse group of people living in the local village – baker, farmer, gardener, carpenter, piano tuner, bricklayer, painter, etc.

- Significant to children. Young children need to feel important. In past eras children were responsible to water the garden, do farm chores, and care for younger children. Children need to feel that what they do is meaningful to someone besides themselves.

- Places children can call their own. A basic human need is the need to belong. Children need to feel they belong, too. They need to be close to people they know, have familiar and comfortable objects, and be in a setting that has a personal history for them.

How teachers can create effective learning environments

The components of a learning environment are many and can be overwhelming. What should an environment for young children look like? How do you create an environment that supports learning and meets children’s basic needs? Below is a brief description of the most important components needed to make an effective learning environment for young children.

Environments for young children stimulate learning

Environments for young children should provide multiple sources of stimulation to encourage the development of physical, cognitive, emotional, and social skills. As you plan your environment, be sure to include the following:

- Places for developmentally appropriate physical activities. Environments should provide children with opportunities for a lot of developmentally appropriate physical activities. Young children are physical beings. They learn most effectively through total physical involvement and require a high level of physical activity, variety, and stimulus change (Hale, 1994).

- Opportunities for concrete, hands-on activities. Young children need hands-on activities – playing in water, building mud pies, making things out of wood, putting a doll to bed, etc. They also need lots of ways to practice and integrate new experiences into existing mental structures – dramatic play, drawing, taking photographs, using language, and making things with blocks.

- Change and variety. Children seek out a constant change of stimuli – scenery, textures, colours, social groups, activities, environments, sounds, and smells. The more our children spend time in our programmes, the more variation and stimulation they need.

- Colour and decorations. Colour and decorations should be used to support the various functional areas in the classroom and centre, provide needed stimulus change and variety, and develop different areas and moods in the room. Vibrant colours such as red, magenta, and yellow work well in the gross motor area; soothing blues and green are good colour choices for hands-on learning centres; and whites and very light colours are good for areas that need lots of concentration and light. Soft pastels and other gentle hues, on the other hand, work well in reading areas and other low intensity activities. Decorations should follow the same pattern, with an additional emphasis on changing them often, and providing order around topics, projects, and themes.

Materials and equipment contribute to the overall environment and programme philosophy

The success of an early childhood environment is not dependent upon aesthetics and design alone. The materials and equipment given to the children are just as important to learning as the physical space of the classroom. The following materials and equipment can be added to any early childhood environment.

- Soft, responsive environments. Children who spend most of their day in one environment need surfaces that respond to them, not hard surfaces that they must conform to. Sand, water, grass, rugs and pillows, and the lap of a caregiver respond to a child’s basic physical needs (Prescott, 1994).

- Flexible materials and equipment. Children can use sand, water, or play dough in a variety of ways, depending on their maturity, ability, past experience with the materials, interest, and involvement. A jigsaw puzzle, on the other hand, has only one correct solution. Legos® and tinker toys have specific physical qualities that must be adhered to, but are also flexible enough to allow a range of creative activities. Programmes should include lots of materials that have an abundance and variety of uses to give children a sense of creativity and control (Wardle, 1999).

- Simple, complex and super complex units. According to Prescott (1994), learning materials can be simple, complex, or super complex. Simple materials are those with essentially one function, complex those with two, and super complex, those with more than two. For example, a pile of sand is a simple unit. If one adds a plastic shovel to the sand it becomes a complex unit. Adding a bucket of water or collection of toy animals to the sand and shovel creates a super-complex unit. The more complex the materials, the more play and learning they provide (Wardle, 1999).

Strategies for small spaces

Programmes with little space must change their areas often and find creative ways to use community areas such as parks and recreation facilities for gross motor activities. With a little creativity, small spaces can work out very well. For example, I once observed a very well planned and supportive early childhood environment designed under the bleachers of a high school! Lofts were built, there were cosy reading areas, and each Head Start child had a place of their own. When I was teaching in Kansas City, we walked across the street to use the Jewish Community centre's gym and swimming pool. When using community facilities, be sure that playgrounds and other equipment are safe and developmentally appropriate for the children in your care.

Private places

Because so many child care facilities have limited space, it can be challenging to respond to the uniqueness of each child within a collective environment. Young children have unique personalities and needs that require us to respond to them as individuals, not as members of a group. The environment must be responsive to this need. Ease of cleaning, maintenance, supervision, cost, and adult aesthetics should not detract from providing spaces children feel are designed for them. Children need to have private areas, secluded corners, lofts, and odd-shaped enclosures. Individual cubbies for each child's clothes and belongings, photographs of home and family, and at least a couple of secluded areas where two or three children can gather allow children opportunities to maintain their individuality and break away from the group to avoid over-stimulation.

Early childhood environments should be functional for both children and teachers

Unlike traditional classrooms, early childhood environments need to support both basic functions and learning activities. Look around your classroom from a child's perspective. Are toilets, sinks, windows, faucets, drinking fountains, mirrors, towel racks, chairs and tables, toothbrush containers, and bulletin boards at the child's level and child-sized? Are classrooms, bathrooms, kitchens, and eating areas close together so that children can develop self-help skills and important autonomous behaviours? Like children, teachers also need to have spaces that are functional. Teachers need to be able to arrange and rearrange their classrooms for various class activities and supervision purposes. Classrooms that include permanent, built-in features such as lofts, playhouses, tables, benches, alcoves, and cubbies can be problematic. These types of fixed features make it difficult for teachers to create areas for gross motor activities, can cause injury in active children, or prevent inclusion of physical activities altogether. Classrooms built as a basic shell work best.

Accommodating children with special needs

Even environments carefully designed and equipped for young children do not meet the needs of children with disabilities. Adaptations must be made carefully for any child with special needs, be they physical challenges, learning disabilities, or emotional issues. Rifton Equipment produces child-size equipment for children with physical disabilities that integrates well with traditional equipment. Braille and large lettering can be used for children with visual impairments, and sign language can be incorporated into the curriculum for those children with hearing impairments. Reducing distractions, glare, and over-stimulation helps accommodate children with ADD and ADHD.

Including diversity

The environment should reflect the importance of children by including examples of their work in progress, finished products, and by displaying images of children. Every child in the programme must see examples of themselves and their family throughout the centre, not just in the classroom. Visual images are an important part of developing a feeling of belonging in all children, so it is important to display pictures of single parent families, grandparent families, and homes of every race and ethnicity, including interracial, multi-ethnic, and adoptive families. The entire centre should also reflect diversity throughout the world: race, ethnicity, languages (not just English and Spanish), art, gender roles, religious ceremonies, shelter, work, traditions, and customs. The goal is for children to be exposed to the rich diversity of the entire world (Wardle, 1992). This is done through artwork, photos, posters, and signs on the wall; books, dolls, parent boards, newsletters, announcements, and magazines; and curricula materials such as puzzles, people sets, activity books, music, art materials, artefacts in the dramatic play area, and fabrics.

Obstacles to consider when planning your learning environment

When setting up an effective pre-school classroom, a variety of factors must be carefully considered and balanced (Olds, 1982). Below are some of the critical environmental issues that must be carefully addressed as you plan the environment.

- Storage. Storage areas are a little like entrances and exits – they receive lots of traffic and are noisy and congested. For these reasons, storage areas can sometimes foster disruptive behaviour and noise. Provide easy access to materials, allowing children to get what they need quietly and easily. The closer materials are to where they will be used, the better. Storage must also be designed so that materials for independent child use are separate from those teachers control.

- Activity area access. Activity areas need to be located next to supplies and be easy to clean up. The classic example is the art area. While providing easy access to paint, easels, paper, and brushes, the art area needs to be close to a water source and on a surface that can withstand a mess. Similarly, the reading area must be close to book shelves, magazine racks, and comfortable places to sit.

- Noise. Managing noise is important in a classroom. Placing carpet on the floor absorbs noise as does absorbent tile on the ceiling. The reading centre should be next to a quiet area like the art area. Blocks are loud, and should be located next to other loud areas such as the woodworking bench. Noisy activities can also be placed in transition areas or moved outside in good weather.

- Dividers. Dividers are any physical objects that serve to delineate areas within a classroom, create interest areas, control traffic, and distribute children throughout the classroom. Almost anything can be used as a divider, so long as it is safe: shelves, couches, fabric hung from a line, streamers attached to the ceiling, folding screens, puppet stages, etc. Safety is obviously a critical issue. Some dividers are easy to push over. The larger and heavier they are at the bottom, the safer. A divider can also be secured by fastening it to the floor or a wall. Several equipment companies have introduced dividers that attach directly to storage units and furniture. Ideally, dividers should be multi-functional for use as storage units, play furniture, and display boards. Keep in mind that solid dividers or walls of more than 30-40 inches high disrupt the circulation of air in the classroom and limit supervision of children. Less solid dividers, like fabric, avoid this problem. One teacher creatively used colourful fabric streamers attached to the ceiling as effective dividers.

Evaluating the environment

The early childhood environment needs to be carefully evaluated and assessed on an annual basis. There are a variety of instruments available, including evaluations from NAEYC and Head Start, the Early Childhood Environmental Rating Scale by Clifford and Harms (1998), and a variety of other checklists. In conducting the evaluation consider these things:

- Carefully select the person who will conduct the evaluation. The person should be objective and familiar with the programme and children.

- Evaluate the entire centre, including the playground, hallways, and bathrooms. It makes little sense for a programme to have a nice, cosy, intimate classroom, with learning centres and children's work displayed everywhere, and long, cold institutional corridors and large bathrooms with adult-size urinals (Wardle, 1989).

- Make sure all the important objectives of the programme are addressed. Most instruments list each objective and items that support those objectives.

- Be particularly attentive to ways the environment supports new programme objectives. If the programme just added a technology objective, are there enough computers and a well-equipped computer learning centre?

- Ensure consistency. If the programme stresses developmentally appropriate practice and play, then the computer component cannot be designed to support teacher directed instruction and drill/skill activities.

- Balance what we know to be good for children with the new fixation on academics. Many public schools and Head Start programmes are emphasizing teacher directed instruction in academics at the expense of meeting all the children's needs.

- Make sure environments designed to support diversity address all forms of diversity. It is as important for an all-minority programme to show racial, ethnic, and national diversity as a white programme; gender, language, religion, ability, and occupational diversity should all be evident (Wardle, 1992).

Once the evaluation is completed, the results should be tabulated, analysed, and communicated to the programme's decision-makers. The information gained from an evaluation is extremely valuable and can be used to design new programmes and offerings as well as construct the budget for the coming school year.

Conclusion

A good early childhood environment meets the child's basic needs and supports and encourages children to engage in activities that implement the programme's curriculum. Further, the environment is designed to enable staff to facilitate the optimum learning for their children. Finally, the environment makes parents and guardians feel welcome, involved, and empowered.

References

Greenman, J. (1988). Caring Spaces, Learning Places: Children's environments that work. Redmond, WA: Exchange Press.

Hale, J. E. (1994). Unbank the Fire. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Harms, T., and Clifford, R. M. (1998). Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Olds, A. (1982). Planning a Developmentally Optimal Day Care Centre. Day Care and Early Education. Summer.

Prescott, E. (1994). The physical environment – a powerful regulator of experience. Child Care Information Exchange,100, Nov/Dec. 9-15

Shore, R. (1997). Rethinking the Brain. New York, NY: Families and Work Institute.

Wardle, F. (1989). Case against Public School Early Childhood Programmes. ERIC #ED310846

Wardle, F. (1992). Problems with Head Start's Multicultural Principles. Manuscript. Denver, Co.

Wardle, F. (1999). Educational Toys. Early Childhood NEWS (Jan/Feb). 38.

Reprinted with permission of Early Childhood News: the Professional Resource for Teachers and Parents