Better building design for young children

| June 2006Architects are currently enjoying the biggest programme of building for young children that this country has ever seen. But whether the results will produce corresponding educational benefits is an open question.

From the 1920s, pioneer architects established a fine tradition of nursery design based on sensitive understanding of small children’s needs rather than a desire for grand architectural gestures. Little was built between the early 1970s and the late 1990s, but today the trickle is turning into a flood. CABE and the DfES have recently produced new design guidance, but it is clear from the experience of both ELE (at planning stage) and Community Playthings (during implementation) that many architects underestimate the design challenge of early years. These include the distinctive educational and organisational requirements of the Foundation Stage of the National Curriculum; the importance of the whole environment – indoors and outdoors – for experiential, interactive learning; the SEN and Disability Act 2001; and the need to integrate education, childcare, family support, adult training, health and other services in children’s settings.

Whilst working with childcare professionals, we meet some who are happy with their buildings but also many who are frustrated, wishing their architects had better understood how young children learn. Children are not simply undeveloped adults; they have unique needs and ways of learning that must be considered from the outset, and they can either benefit from or be frustrated by their environment. A good early years setting is very different from a school; the younger children’s activities are not desk-oriented or teacher-directed, but floor-oriented and chiefly based on child-initiated play.

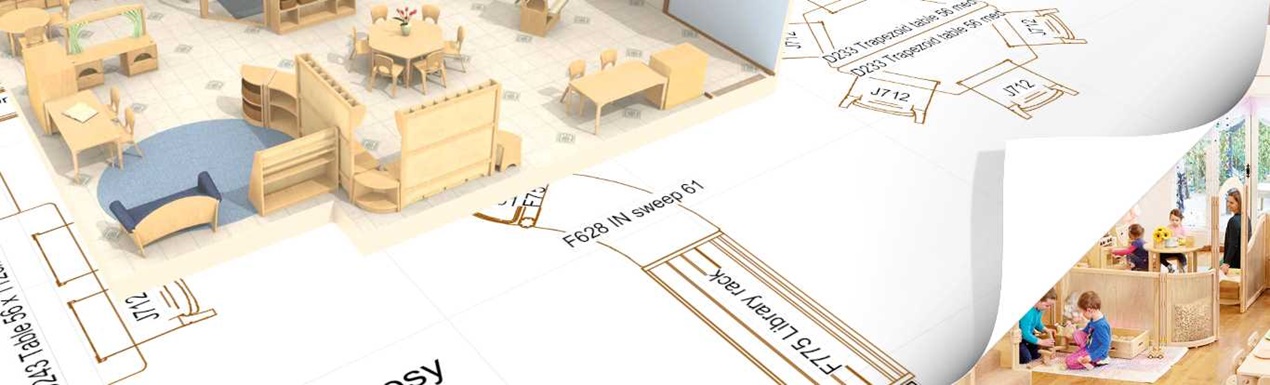

Designing a well-planned playroom

Exploring all these issues is beyond the scope of a single article, but central to young children’s learning, development and welfare is a well-planned playroom. Below are some of the key considerations.

Amount of space

There must be sufficient space for the children and their activities, for staff, and sometimes for parents too. Childcare practitioners prefer open space to special features such as extra partitions or unusual angles. The government has regulated minimum space per child at various ages, but it must be stressed that this is the minimum and is not meant as the standard! The minimum required space for a group of six three-year-olds for full nursery care is 13.8 square meters, but a room that small is simply non-functional for six children!

The DfES has prescribed six areas of learning for which nurseries must provide space for three- to five-year-olds. The activities that support these areas of learning are based on play, which occurs simultaneously in several activity areas throughout a room. Typically a nursery will include a construction area where children build roads and houses with blocks; a cosy book corner; a large role play area where children enact family or surgery or whatever inspires them that day; a creative art area near the sink with easels and tables to support children’s artwork as well as shelves to store paper and craft supplies; a science/discovery area with perhaps some sand and water tables and display units; tables for puzzles and practice of writing skills; floor space for music and movement; an eating area; and (if younger children are included) a quiet area or adjacent room for sleep. This should help architects understand the need for ample space!

Shape of room

There is an architectural trend away from rectangular rooms, but unless the new shape gives children more playing space, it is detrimental. Sometimes architects win prizes for amazing circular buildings – but the children lose out! The beauty of a rectangle is its corners. To free the corners for activity areas, any door should ideally be in the centre of a wall. Stick with the minimum number of doors per room, as they take space and generate traffic, and use double doors only if absolutely necessary.

Flexible set-up

Versatility in the physical set-up is essential. It supports:

- Varying numbers of children

- Varying ages of children

- Inclusion of children with special needs

- Children’s control of their environment

- Changing staff with differing preferences

- Changing educational themes

- Varying functions of space (after school club, community activities, etc.)

Built-in storage units prevent adaptation of rooms and curtail play space, but we frequently receive architectural plans with large storage closets protruding into the playroom. Educators often prefer mobile shelving, with which they create natural boundaries for activity areas (shielding children’s play from through-traffic) and supply materials to children at point of use. Shelves holding bricks and accessories would bound the children’s construction area, for example. Storage cupboards lining an entire wall make it difficult to create a child-friendly setup; any activity taking place along that side of the room will be disrupted by traffic to and from the supply cupboards. Where additional classroom wall storage is required, choose wall cupboards that can be relocated around the room, and are child-accessible while providing secure, teacher-accessible storage above.

Not only storage units, but any built-in features prescribe the use of the space and are a potential future nuisance. I visited a nursery where a sand pit had been built into the centre of the room, locking the nursery into one permanent arrangement. Similarly, built-in ICT units and built-in coat hooks create problems nearly every time we encounter them in our room-planning service. Practitioners want to be able to decide for themselves the arrangement of their rooms.

Floor surfaces, too, should accommodate future change in room layouts. Vinyl, lino or other non-slip flooring is preferable to carpet, so staff can situate wet or messy activities – including meals – where they wish. It’s easy for them to move a rug if they later decide to change the location of the book corner. A purpose-built Early Excellence Centre in Somerset ripped out their carpets within months of opening and re-did the entire floor with vinyl!

Functionality of space

As architect Robin Bishop states in his article, Better Design for Young Children, “a good standard of building and a sensitivity to small children’s needs is worth far more than ephemeral wow-factors.”

There needs to be direct access from playrooms to the outdoor play area, as children flow in and out all day. Toilet and nappy-changing facilities must be easily accessible from both indoor and outdoor areas. A nappy-change unit with steps is commendable for the sake of carers’ backs.

Display is essential in a children’s setting because of the positive reinforcement children gain from seeing their work respected, and because best practice asserts that children’s thinking is developed and extended over time if it is visibly documented (often through photos of the creative process). So wall space is at a premium.

A balance is important in the use of glass. Natural light is wonderful, and children enjoy looking out; but too much glass creates a harsh environment, uses valuable wall space, and makes children feel exposed. Visiting one site for which we had done the furniture layout, we were dismayed to discover that the outside walls were almost entirely of glass – it would have made a fine office complex but was hardly an appropriate environment for children. Noise ricocheted through the setting and it was almost impossible for staff to create cosy spaces or display children’s work on the walls. I visited another centre in London where the head teacher noticed that in winter children never played near the French doors that comprised one side of the room – it was simply too cold on the floor, where children generally play.

An outdoor porch or covered play area is essential to support large-motor activity in any weather. It provides a link or transition between outdoor and indoor play areas. (It does not replace the garden, which fills other needs.) Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget said that movement is the bedrock of all intellectual learning. Young children must have places to make noise and partake in active movement of every kind!

Conclusion

Young children need security, and they need adventure. They need stimulation, and they need quiet. Children have tremendous physical, mental, and emotional energy, which needs to thrive in creative ways. It is a challenge for both architect and childcare practitioner to create an environment where all these aspects come together in a positive way! The time invested in planning a child-friendly place is well spent, because, as Maria Montessori said, ‘Adults admire their environment; they can remember it and think about it – but a child absorbs it. The things he sees are not just remembered; they form part of his soul.’

References

Bishop, R. (2004) ‘Better Design for Young Children,’ Early Education, British Association for Early Childhood Education

Community Playthings (2002) Spaces – Room Layout for Early Childhood Education

Community Playthings (2005) Creating Places for Birth to Threes – Room Layout and Equipment

DfES Building for Sure Start: Integrated Provision for Under-Fives

DfES National Standards for Full Day Care

Dudek, M. (2001) Building for Young Children, National Early Years Network

Reprinted from book with permission from the National Children’s Bureau. Copies available from the NCB on 0207 843 6029.

Effective Learning Environments website www.eleuk.com

Greenman, J. (1988) Caring Spaces, Learning Places: Children’s Environments that Work, Exchange Press Inc.

Olds, A. (2000) Child Care Design Guide, McGraw-Hill

Ryan, P. Your Montessori Child, London: Montessori International